By Ayanda Tshabalala*

This blog post is based on a conference paper which was presented at FWSA (Feminist and Woman’s Studies Association) Biennial Conference 2015 – 9 Sept 2015 and based on my Masters dissertation at UKZN (University of KwaZulu-Natal).[1]

This post will also be found on the FWSA blog site.

The FWSA Conference offered great exposure to global thought and helped set the tone for future conversations I’d like to have about issues of gender through the platform of academia. Issues of different forms of violence towards gender groups that were discussed at the conference were honestly emotionally draining. This reminded me that, to a greater degree, research exists because we, as human beings exists, it’s all interconnected and therefore we are allowed to be emotional.

If you’d like to know more about my personal experience at the Leeds FWSA conference, follow my personal website link: http://ayandatshabalala.wix.com/wathintaimbokodo

The conference presentation

Brief motivation/Background

The identity of the Black African woman is influenced by a number of factors in our society including the legacies of colonialism and racism which have contributed to pressure and societal expectations. Possibly reflective of this, recent press reports and anecdotal evidence suggest a rising trend of Black African women aspiring towards lighter skin or broadly choosing notions of beauty that are associated with the self-image of people who are of the White race. This includes Black African women wearing long synthetic hair and using creams to bleach their skins so as to appear “whiter” in complexion. The skin bleaching practise in Africa is attracting international journalistic attention (Pierre, 2008). The major discussions about the practise are its medical, psychosocial or cultural implications. However, very little academic work exists on this topic generally in Africa, and specifically in South Africa. Broadly, this research paper to which this blog is based aims at attempting to fill this gap, by investigating the reasons behind the practise among young Black African women in South Africa.

This paper investigates the controversial notion of racial capital among modern, young Black African women and how racial capital is influenced by the commodification of their cultures. According to Hunter (2011), racial capital describes how a lighter skin tone can be used as a form of social capital, symbolic capital, and economic capital. The research interrogates the notion of racial capital in the context of skin-bleaching practises among Black African women in South Africa. In addition, the paper investigates skin bleaching practises in the context of gender expectations in society which also contribute to the self-image of Black African women. Consequently, the research was informed by a critical feminist perspective.

Explicitly in this context, feminism is a movement that is geared towards ending sexism and sexual exploitation or oppression of all forms and against all genders. More than wanting what men have, critical feminism adopts notions that challenge existing cultures without looking to fit in a sexist environment (Hooks, 1984, 2000).

Review of Literature

According to Blay (2011), the introduction and positioning of Christianity through colonialism in African countries socially constructed this doctrine as a hegemonic ideology that controlled the economic functioning of these societies. The Christian religion and doctrine is expressed in a dualistic manner of white versus black imagery through the presentation of a White Christ. This association of a White Christ as a god led to the white colour being internalised by the African citizens as a colour of godliness and high moral standing. The religion in itself associates the colour black with darkness, damnation, evil and immorality (Blay, 2011). Christianity served as an ideological platform to which Europeans also aspired. In trying to understand the phenomenon of skin bleaching, it is important to therefore understand its relationship with colonialism because the history of skin bleaching began with the European colonizers themselves. Striving to be “Christ-like” even in appearance, European women with whiter skins were being considered more desirable than those with darker skin tones. The appearance of whiteness affected all women during the nineteenth century across all cultures and races as they made some cosmetic efforts to whiten their skins through various practices (Blay, 2011). The use of skin lightning creams amongst Black South Africans heightened during Apartheid as the institutionalization of racism became further rooted in the social and economic laws of the country (Thomas, 2012).

In 1969, a marketing survey was conducted among urban Black South African women and the findings found that skin lightning creams were in the top five of the most commonly used household products, subsequent to the introduction of mass production of skin lighteners in 1960 (Thomas, 2012). This widespread phenomenon increased over the last two decades globally because a lighter skin is still perceived as ‘racial capital’ that gains one a desired economic and social status (Hunter, 2011). Some attribute the increase of skin bleaching to the increase in accessibility to mass media, which presents “ideal” beauty mostly as white physical features. Hunter (2011:144) further elaborates on this and adds: “Images of White beauty do not simply rely on White women with blonde hair and light eyes to sell products. Images of white beauty sell much more than beauty ideals or fashions for women around the globe. Taken as a whole, images of White beauty sell an entire lifestyle imbued with racial meaning”.

In the case of South Africa, racial capital exists in a society that already has established racial hierarchies regardless of whether they are occurring historically or in present times. It describes any process the body is taken through in an attempt to attain “white beauty”. Racial capital also has been elevated to a level of transnational racial significance expanding outside of the boundaries of local ideologies of race (Pierre, 2008). The commodification of the body or race is transformed into an asset that assists one to climb higher in social, economic and symbolic hierarchies. The body or race is mostly used to change self-perception as well as perception of those around them as a mechanism to gain social positioning (Hunter, 2011:145).

In countries such as South Africa, in an era of post-Apartheid, it is perhaps surprising to find the continued practise of skin bleaching when the country is seemingly making efforts to support women empowerment. Black African women are particularly encouraged to participate through initiatives such as Black Economic Empowerment and Affirmative Action. According to Hunter (2011) these failed empowerment initiatives could be as a result of globalisation and a growing globalised job market with intense competition with females of other races. Urban Black South African women may also practise skin bleaching due to the competition in the local job market with women from their own racial group and other racial groups. This practise therefore could reflect how the realities of racial discrimination are still prevalent in our society regardless of implemented social policies such as the above mentioned Black Economic Empowerment that seeks to redress such behaviour.

Modification practises have become some of the most hazardous body modification methods especially when the bleaching creams are mixed with household chemicals such as: toothpaste, washing powder, and battery acid (Lewis et al., 2012). According to a study on skin lightening creams in Durban, South Africa (Dlova, Hendricks and Martincgh; 2012), long-term use of the creams containing mercury and hydroquinone resulted in acquiring the disease, ochronisis, as well as permanent skin damage. In this study, ten of the most popular commercial skin lighteners were chosen and they were easily accessible (to both men and women) in supermarkets, cosmetic shops and street hawkers. The study focused on the medical consequences of using skin lighteners and it also investigated which of the creams had hazardous chemical components such as mercury. The study found that the top-selling creams in Durban contained illegal substances such as mercury and hydroquinone. Six out of the ten top-selling creams were manufactured within South Africa and the other four creams were illegally imported from Taiwan, Italy and the United Kingdom (Dlova et al.; 2012).

Despite the hazardous components of these creams, I was interested to know whether UKZN students were users and there reasons for use. My research question was: Why do young Black African women in South Africa use skin bleaching creams?

Methodology

The study used a qualitative exploratory research design (MacMillan et al., 2010).

The primary source of data collection was through audio recorded interviews conducted in a face-to-face format. An interview schedule was prepared with pre-defined questions. The interviews were digitally recorded and later transcribed and thematically analysed. The sample was composed of 20-30 young Black women who are currently students at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. Young Black female University students were chosen who had varying skin tones.

Brief Preliminary Findings

From the conception of the study the concern was the sensitivity of the inquiring about skin bleaching. A large focus was therefore placed on interpreting the perceptions towards the skin bleaching practise. Below describe the preliminary findings around respondents’ perceptions around skin tone, the use of skin whitening products and self-perceptions around racism.

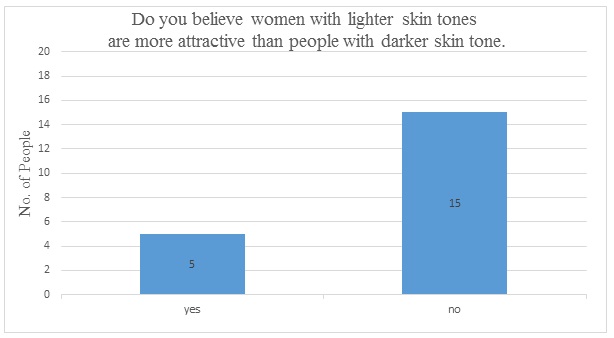

In Figure 1, findings show that most of the respondents (15 out of 20) disagree with the beliefs that women with lighter skin tones are more attractive to women with darker skin tones.

Figure 1: Perceptions of attractiveness to women’s skin tone

Source: Author

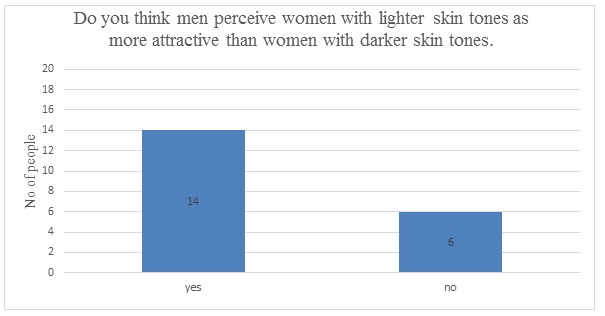

Women’s perceptions were then compared to the respondents’ perceptions of what skin tone men would prefer. In Figure 2, the findings show the reverse of the findings in Figure 1; 14 of the 20 respondents believed that men perceive women with lighter skin tones as more attractive than women with darker skin tones.

Figure 2: Perceived attractiveness by men based on women skin tone

Source: Author

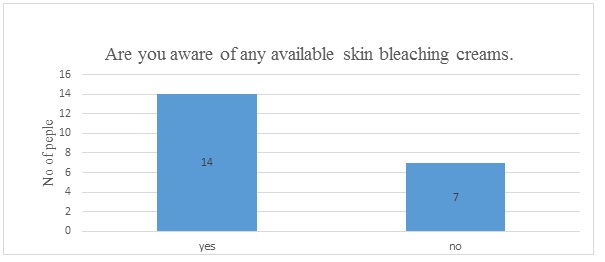

In Figure 3, the findings show that most of the respondents were aware of available skin bleaching creams and their responses correlated with the study that was conducted in Durban by Dlova et al, (2012). Many of the products the respondents were aware of were found in the informal business sector such as through street vendors.

Figure 3: Awareness of the availability of skin lightening creams

Source: Author

Below are some quotes from local South African celebrities who are publicly known and have declared to be using skin bleachers:

“I’ve been black and dark-skinned for many years; I wanted to see the other side. I wanted to see what it would be like to be white and I’m happy.” Mshoza

“Ima BLEACH until Jesus Comes, you are too damn stupid to think that your opinion matters…I have never asked to be anyone’s role model. No one I mean no one has a right to impose their believes on me I’m my own person, living my life and I will do as I please… so please don’t tie me down with all this nonsense of people looking up to me. It’s their choice I never asked them.” Kelly

Findings on the health implications of practising skin lightening

Respondents were asked about their awareness of health issues associated with the skin lightening products available in the market. Only one of the 20 is practising skin bleaching, and four chose not to answer. The reasons given by the respondent for practising skin bleaching included: “nicer skin’; “family uses it”, “for even toned skin and prevents break outs.” When the respondent was questioned about the known and experienced side effects, she said:

“[…] can’t be exposed to sunlight a lot or I will get darker again, and get spot,”Respondent.

Findings on Racism

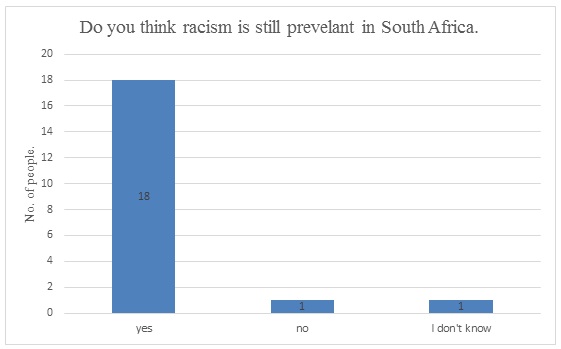

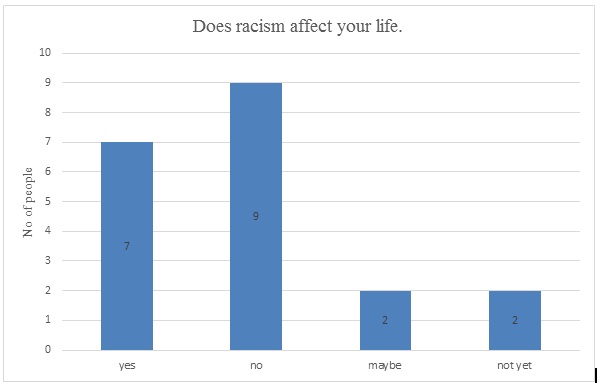

The respondents’ age group meant they were raised in Post-Apartheid South Africa and issues of race are still prevalent in the country. It was interesting to that most of the respondents agreed that racism was still prevalent in South Africa (Figure 4), but the majority of the respondents felt racism did not affect their current lives (Figure 5).

Figure 4: Participants’ perceptions of racism

Source: Author

Figure 5: Self – perception of racism

Source: Author

Concluding Remarks

I am currently completing the data analysis stage of the study which is yielding further results, some of which are correlating with the explored literature and others which are contradicting the current available research. Above- all, the research objectives for the study were met and elaborations were found that contributed to the objectives. By the end of this year, a better understanding will be available in the exploration of why young Black women at the University of KwaZulu-Natal may be practising the act of skin bleaching.

[1] Full citation of the conference proceedings:

Tshabalala, A. (2015). Why do young Black African women in South Africa use skin bleaching creams? A study of students at the University of KwaZulu-Natal. Presented at the Feminist and Women’s studies association Binennial Conference 2015, Leeds University 9-11 Sept 2015.

*Author’s Bio: Ayanda Tshabalala is an emerging young South African academic and passionate gender activist. She holds a Bachelor of Social Sciences degree (Marketing, Media and Management) from the University of KwaZulu-Natal (Durban, South Africa); and is currently completing a MA in Development Studies. She is research assistant for Professor Sarah Bracking under the DST/NRF South African Chair Initiative (SARChI) in Applied Poverty Reduction Assessment. Ms Tshabalala received full travel funding from the SARChI to present her work at FWSA. Any opinion, finding and conclusion or recommendation expressed in this material is that of the author(s) and the NRF does not accept any liability in this regard.

You can reach Ayanda at: ayandatshabalala@yahoo.com; or inbox through her website: http://ayandatshabalala.wix.com/wathintaimbokodo.

Bibliography

Blay, Y. 2011. Skin Bleaching and Global White Supremacy: By way of Introduction. The Journal of Pan African Studies. 4(4): 4-45.

Dlova, N.; Hendricks, N. and Martincgh, B. 2012. Skin-Lightening creams used in Durban, South Africa. International Journal of Dermatology: 51-53.

Dlova, N., Hamed, S., Tsoka-Gwegweni, J., Grobler, A., & Hift, R. (2014). Women’s perceptions of the benefits and the risks of skin-lightening creams in two South African communities. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology, 13, 236-241.

Hooks, B. (1984). Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center. Boston: South End Press.

Hooks, B. (2000). Feminism is for everybody: Passionate politics. Cambridge, MA : South End Press .

Hunter, M. 2011. Buying Racial Capital: Skin-Bleaching and Cosmetic Surgery in a Globalized World. The Journal of Pan African Studies. 4(4): 142-163.

Lewis, K., Robkin, N., & Njoki, L. C. (2011). Investigating Motivations for Women’s Skin Bleaching in Tanzania. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35(1), 29-37.

McMillan, J.H, and Schumacher, S. 2010. Research In Education. Evidence-Based Inquiry. New Jersey: Pearson.